Update 84: Key Questions to Ask if in the Hospital for COVID-19 (Part 1 of 2)

本文由‘中国推动’学者、江南大学药学院石漱新同学编辑整理。

Welcome to another MedCram COVID-19 update.

I wanted to talk to you today about the unthinkable. What would happen if you or your loved one had to be admitted to the hospital for coronavirus COVID-19? What are the right questions to ask? Are they doing everything right? What does all this information mean? I wanted to put together a little bit of a primer course for you here on this video, so you can understand what it is that’s actually going on, and so you can ask the right questions.

So, the first step is if the patient is sick enough to go to the emergency room, and emergency room doctor is going to evaluate the patient and decide whether or not the patient needs to be admitted or not. This is typically based on oxygen requirement. How much oxygen is necessary to keep the patient’s saturation up. If the answer is that they don’t need to stay in the hospital, then they go home, and probably this means isolation.

If the answer is yes, there’s many different places this patient could go in the hospital depending on the severity of illness. First one is known as med surg. This is probably one of the lowest areas of admission in terms of acuity. Generally here, there is 4 patients to a nurse, they’re not usually checking pulse rhythms, heart rhythms and oxygenation continuously. Rarely, if someone with COVID-19

is gonna be admitted to the hospital, what they need to go to (is) med surg. Generally speaking, they would go where they could measure their oxygen. The next step up is something called telemetry. This is where you are continuously monitoring somebody with the device that they wear on their chests in terms of leads. This would be monitoring their heart rate. This will be monitoring their EKG Rhythm. This will be monitoring their oxygen saturation and also checking blood pressure every once in a while. Here again, it’s typically 4 patients to a nurse.

Sometimes there is an intermediate step but then next would be I see you here, there are 2 patients per nurse. And this is where you would have patients on ventilators on BiPAP. We’ll talk about that in a little bit. Generally speaking, you’ll be admitted to med surg with a hospitalist, to telemetry with a hospitalist, to intensive care with a hospitalist, and or you may have an intensivist or critical care physician on the case. Also, generally speaking, you could have consultants which are experts in the field of

Nephrology, Cardiology (and) infectious disease.

I will make a note here that once someone, generally speaking, gets admitted to the hospital. That’s the hospital that they’re pretty much going to stay at, unless there’s something that they need that is not at that hospital. And then that’s called a transfer process. Usually, it’s much easier to transfer somebody to another hospital out of the emergency room than it is after the patient becomes admitted. So, it’s really important for doctors when they’re admitting a patient to the hospital to make sure that they have all the things that

they need at that hospital to take care of that patient. It’s also the reason why I advise patients that if they get into trouble, try to pick the hospital that they go to carefully because if they go to a hospital that doesn’t have all of that equipment, it’s usually difficult to transfer the patient afterwards. So, one of the questions that I would ask is if you know someone’s being admitted to the hospital, are they going to med surg? Are hey going to telemetry or they go into intensive care unit? Obviously, intensive care patients are much more sick than med-surge or telemetry patients.

Let’s talk about oxygen. As you already know, oxygen is very important for the human body. Without it, you can’t metabolize very well, you can’t have an electron transport chain, you cannot make ATP. So oxygen is really a function here in terms of coronavirus of how much oxygen you’re giving the patient and how much oxygen is getting into the blood. Obviously, you want to give a small amount of oxygen and have a large amount of oxygen in the blood, but that can change as the coronavirus causes problems

in the lungs.

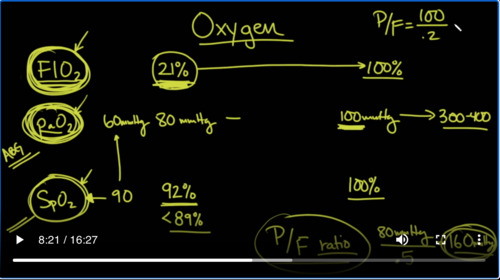

So, a couple of definitions that you need to know, something called the FIO2 and basically it’s by volume how much of the air the patient is breathing in is oxygen. Now, normal is 21%, that’s what you’re breathing right now up sensibly. If you don’t have any oxygen on your face and you’re just breathing the air in the room right now, 21%, and that can of course go up all the way to100%.

Another term that you should know is something called the PaO2. The PaO2 is the partial pressure of oxygen in the bloodstream. And generally speaking, a normal value would be anywhere from 80mmHg to 100mmHg. Now, there’s another way of looking that and that’s the saturation, that’s the SpO2. And SpO2, generally, is

how well is the hemoglobin molecule circulating in the blood, how well is it saturated. Generally speaking, we like to see that around 92% all the way up to100%.

The SpO2 is something that you can actually see on a pulse oximeter. That’s a little device that you can wear on your finger and you can see it for yourself. If this number is dipping below 90, let’s say you go out and buy one of these things and you put it on your finger, you’ll see that it can sometimes dip below 90, especially if it’s high altitude. But this can also happen in pneumonia in ARDS in COVID-19, coronavirus. Put it on your finger, if it’s low that’s usually a sign that you’re sick enough to

need oxygen. And generally speaking, the hard-and-fast rule is if this is less than 89%, you are going to require some oxygen. And that’s when you need to go to the hospital if not before. So the SpO2 is something that we can read in real time. It’s at the bedside on the patient monitor and we can see what their saturation is. Again, we tend to target somewhere in the 90s here. The PaO2 can correlate with this, as saturation of

90 generally correlates with a PaO2 of 60 mmHg. And of course the PaO2, if you put somebody on 100% oxygen, this can go up to as high as 300 or even 400 in some cases, pretty high up. And of course that’s if we turn up the FIO2. So you can see something here without getting too confused. FIO2 is kind of like how hard you hit the gas pedal on a car. And the PaO2 and the

SpO2 are kind of like the speedometer in miles and kilometers, I’m just saying this very roughly. If you have a very powerful car, you don’t have to hit the gas that much to get great oxygen air or great speed on the car. But as the car starts to become more and more sick, you’ll start to see that you’re going to have to give a little bit more touch on the pedal to get the same kind of speed that you were used to before. And so there’s a way of actually putting that together. It’s known as the

P/F ratio. By the way, the PaO2 can only be gotten on something called that an arterial blood gas. That’s where they actually poke your wrist to get arterial blood. The SpO2, on the other hand, can be gotten just off of a finger probe that they can actually tell what the saturation is. But to get a P/F ratio, you’re going to get a PaO2 and an FIO2. And so here, PaO2 could be something for instance like 80

mmHg devided by, let’s say, we have you on 50% FIO2, then that would be divided by 0.5. And therefore a P/Fratio in this case would be 160mmHg. That would be the P/F ratio. Now, why is that important? Well, the P/Fratio kind of tells you how well the lungs are working in terms of delivering oxygen into the blood stream. You can imagine that somebody who is normal like you and I, watching this video.

Well, you would have a P/F ratio of what, let’s pick a nice even number, let’s say, 100 divided by 0.21 or let’s say 0.2. So that would be100 divided by 0.2, would be equal to 500. So you can see here that as the number goes down to 160 for instance from 500, the lungs are getting worse and worse and worse. In other words as it takes more and more oxygen to get a good PaO2.

The P/F ratio is going to drop.

So, as we’ve already said a normal P/F ratio would be around 500. Where we start to get into issues with COVID-19, mild ARDS, that we would see in COVID-19, would be less than 300, moderate ARDS would be less than 200 and severe ARDS would be less than 100.

So in other words, if I was getting a PaO2 of 100mmHg, but I had the patient on 100% FIO2 or 1.0 In this case, that would mean that I would have severe ARDS consistent with COVID-19. So one of the things that you can ask is what’s your P/F ratio and if they don’t know what that is, you can educate them on what that is and that’s simply the PaO2 on the blood gas that they have to poke your

wrist with, divided by the amount of oxygen that you were on at the time, and that’ll tell you in this scale, how bad the ARDS is with your lungs.

Now, this is a great slide. We got this from EMcrit.org and we will put the link in the description below. But you can see here, based on the FIO2 requirement, in other words, how hard you have to hit that pedal, you can see how much oxygen is going to be needed. So at the very top, if you just need just a small amount of oxygen

, typically, we’ll do a low flow nasal cannula, set at a certain amount of liters per minute. If you have 0L/min, then you’re breathing 21%. So you got to realize that every time you turn up the leader flow on the oxygen by 1L, that’s about 4% FIO2 increase. So if you, for instance, had somebody on 3L of nasal cannula 3 times for be 12, 12% plus 21%, would be about 33%

FIO2. So that’s one way of checking what the FIO2 is. As you go up to 6L, the low flow nasal cannula, it’s only set up to give about 6L/min. If you need more than that, because the oxygen keeps falling, then you can titrate the FIO2 up and go to a high flow nasal cannula. This is where you’re getting maybe 20, 30, 40 liters of air being pushed into the nostrils and down into your lungs. And of course you can adjust the FIO2

based on how much you need and titrating ,look at the SpO2 titrate, how much auction need to keep the saturations greater than 90. You can also use something called CPAP, which is continuous positive airway pressure or BiPAP, bi-level, bi-positive airway pressure with low driving pressures and you can tolerate that as well and titrate that. Now, one of the things that they are talking about, we’ll talk about this a little bit more, is you can do something called awake pronation. That’s where they flip on their belly. Now, if high flow nasal cannula or CPAP or

BiPAP is not enough, then we move to invasive mechanical ventilation where as we’ve talked about before, we use low tidal volumes allowing the carbon dioxide levels to hang up a little bit more. But the key here is that you can also adjust on the ventilator what the FIO2 is you can go to 100%, 80%, 90%. And then get a blood gas, check the PaO2, look at the FIO2, you’ll have a P/F ratio and you can kind of gauge how bad the lungs are.

Once again here, we’re talking about

prone positioning. As you can see here, they would consider for severe hypoxemia, where the PaO2 divided by the FIO2, this is the P/F ratio, is less than 150. So again, you know that a P/F ratio less than 150 is going to be in the moderate to severe range. And then finally we have this thing called veno-venous ECMO. That’s where we actually take the blood that was going to go to the lungs, take it to a lung machine, scrub the CO2 out of it, put oxygen in and then have it go back and so

the heart can pump it around. That’s basically a heart-lung machine. So you can see here going from the very lowest to the very highest support and then during the recovery phase, how it goes back again.

Okay. So let’s talk about prone positioning. This is what we mean by prone positioning. It’s where you are basically lying on your belly.

In this lateral view of the chest, you can see here the outline of the lungs and if you were to draw a line down the middle, you would notice very quickly that there’s a lot more lung tissue posteriorly toward the back. Then there is anteriorly, especially since you consider the fact that the heart which sits here anteriorly is taking up some of that room. Now, it’s important to understand because when you are lying on your back, fluid that may be accumulating your lungs because of ARDS

Is going to go in the dependent position. So it’s going to fill in this area of the lung, which is larger than anteriorly. And as a result of that, blood also is going to go to that area because of gravity and because the pulmonary artery pressures in patients are pretty low compared to the systolic blood pressures. And what you’ll see is that the blood will go to the area where there is more fluid and also less oxygenation. So with all of this happening, what you’ll notice is that

dependent portions of the lung are not as well aerated as non-dependent portions of the lung when you’re laying on your back. So when you flip over and go to the prone positioning, the areas that are better oxygenated will be getting better perfusion because the blood will always go to the more dependent portions of the lung.

So, to repeat what I just said, there basically in the supine position, that’s where the fluid is going to accumulate and it’s going to prevent you from getting good oxygenation. And that’s also by the way, where the blood vessels tend to send more of the blood in terms of exchange. And so, because of that you’re having a blockage of gas exchange in the area where most of the blood is going, and that could be one of the reasons why, there are other reasons why, too. One of those which is that the heart is sitting here anteriorly and it’s

falling back a little bit and causing some atelectasis of lung tissue. And there’s also other things that they think that may be going on. When you turn over in the prone position, remember that a lot of the lung tissue that we said was up here, had infiltrative changes in it and fluids and that starts to move anteriorly forward, allowing the majority of your lung to be free to exchange gas. And also remember that blood is going to immediately go down and start

perfusing portions of the lung anteriorly that are better off subjugated, have a more open lung strategy and have gas exchange as well. And so typically what we will see is that we will have better SpO2 or saturation in prone positioning. So this is another question to ask the physicians taking care of your loved ones or yourself is whether or not there is prone positioning occurring and to actually call your loved one who’s in the hospital and tell

them to do this because they might not be being told to do this. And it might be well to check with their physician in the hospital to see whether or not they can do this because it can make a difference. And the reason why it can make a difference is that it buys you more time without having to get on to the ventilator. I have seen this in some of my patients where we were getting close to needing to put the patient on a ventilator but because they were proning, we were able to improve their oxygenation to the point where we

were able to delay that or even prevent having to even do it.

Add comment