布洛芬和COVID-19;NSAIDs是否安全?HIV药物治疗试验(第40讲)

Ibuprofen and COVID-19 (Are NSAIDs Safe_), Trials of HIV Medications, Preliminary CDC Fatality Data (Lecture 40)

Welcome to another MedCram covid-19 update. We’ve got a lot of news to cover today. There have been a lot of things that have come back from a medical standpoint. There were over 200,000 total confirmed cases worldwide; total deaths almost 9,000; total recovered 84,000.

欢迎来到MedCram covid-19的另一个更新。今天有很多新闻要报道。从医学的角度来看,已经有很多事情回来了。全世界总共有超过200,000例确诊病例;总死亡人数将近9,000;总共追回了84,000。

If we look country by country on the WorldOmeter site, we can see here only 34 new cases total in China at this point. Most of the cases are outside of China. In fact, more cases in Italy in terms of active cases than there is anywhere else in the world at this point. The United States cases have jumped to almost 10,000. That’s probably because of increased testing that is now coming online in the United States. Despite that, we only have about 64 serious or critical cases in the United States out of a total of 9200.

如果我们在WorldOmeter网站上逐个国家地查看,到此为止,我们在这里只能看到34个新病例。大多数情况在中国境外。实际上,就目前而言,意大利的活跃案件数量超过世界上其他任何地方。美国的案件已增至近10,000起。这可能是由于现在美国在线测试的增加。尽管如此,在美国的9200例中,只有大约64例严重或严重的案例。

We also have news here from the CDC. In their morbidity and mortality weekly report that was released yesterday on March 18, it says that the first preliminary description of the outcomes among patients with covid-19 from the United States indicates that the fatality was highest in persons greater than 85 years of age, ranging from ten to twenty-seven percent; followed by three to eleven percent mortality among persons aged 65 to 84; one to three percent mortality among persons 55 to 64; less than one percent among persons 20 to 54 years of age, and no fatalities among persons less than 19 years of age.

CDC也有新闻。在昨天于3月18日发布的发病率和死亡率每周报告中,该报告指出,对来自美国的covid-19患者的结局进行的第一个初步描述表明,死亡率在85岁以上的人群中最高,百分之十至二十七;其次是65岁至84岁的人群中的3%至11%的死亡率; 55至64岁人口的死亡率为1-3%;在20至54岁的人群中不到1%,在19岁以下的人群中没有死亡。

Here, we see the number of new covid-19 cases reported daily in the United States from February 12 to March 16, and you can see that that has gone up steadily, and here you can see it by age group how many hospitalizations in the light lavender and ICU admissions in the darker blue, and then deaths in the darkest blue. You can see that there is a stepwise increase here in different ages.

在这里,我们可以看到从2月12日至3月16日在美国每天报告的新的covid-19病例数,您可以看到这一数字稳步上升,并且在这里您可以按年龄段查看在美国有多少人住院淡紫色和淡紫色的ICU入场处为深蓝色,然后死亡为最深蓝色。您可以看到,不同年龄段的用户数量都有逐步增加的趋势。

For the greater than 85 years of age, there were more deaths than there were in the intensive care. That may be because of palliative care or hospice, where you have patients that are hospitalized but never go into the Intensive Care Unit before they pass. Here is the breakdown for age groups here in terms of hospitalization percentage, ICU admission percentage, and case fatality percentage.

在超过85岁的年龄段,死亡人数比重症监护病房要多。那可能是由于姑息治疗或临终关怀所致,那里您的患者已经住院但从未经过重症监护病房。以下是按住院率,重症监护病房(ICU)入院率和病死率列出的各个年龄组的细分。

This is the big news that was published today in the New England Journal of Medicine. It was the trial of lopinavir and ritonavir, which are HIV medications in hospitalized adult patients with severe covid-19. This was a trial that was done in China. This was a trial that was a randomized controlled, open-label trial because they couldn’t have time to prepare the placebo pills, and they gave it to randomize patients, of course, to see how they would improve with covid-19.

这是今天在《新英格兰医学杂志》上发表的重大新闻。这是洛匹那韦和利托那韦的试验,洛匹那韦和利托那韦是患有严重covid-19的住院成年患者的HIV药物。这是在中国进行的试验。这项试验是一项随机对照,开放标签的试验,因为他们没有时间准备安慰剂药,他们将其随机分配给患者,当然看看他们如何改善covid-19。

The endpoint here was either discharged from the hospital or an improvement on a seven-point scale, which we’ll talk about. The primary endpoint was the time to clinical improvement defined as the time from randomization to an improvement of two points on a seven category ordinal scale, or live discharged from the hospital, whichever came first.

这里的终点要么是出院,要么是七点制的改善,我们将对此进行讨论。主要终点是达到临床改善的时间,定义为从随机开始改善到七类序数上的两个点的改善或从医院出院的时间,以先到者为准。

The seven-point scale has been used before in other influenza studies. This is the scale. I: If you’re not hospitalized with resumption of normal activities; 2: if not hospitalized, but unable to resume normal activities; 3: hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen; 4: hospitalized, requiring supplemental oxygen; 5: hospitalized, requiring nasal high-flow oxygen therapy, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, or both; 6. Hospitalized requiring ECMO, invasive mechanical ventilation, or both; and 7: death. If there was a movement down of two points, or a discharge from the hospital, that would indicate improvement.

七分制以前曾在其他流感研究中使用过。这是衡量标准。1:如果您没有因恢复正常活动而住院; 2:如果未住院,但无法恢复正常活动; 3:住院,不需要补充氧气; 4:住院,需要补充氧气; 5:住院,需要鼻高流量氧疗,无创机械通气或两者兼而有之; 6.需要ECMO和/或有创机械通气的医院; 7:死亡。如果下降了两点,或者出院了,则表明情况有所改善。

You have 357 participants that were assessed for eligibility. There were some that dropped out, leaving a hundred and ninety-nine, which underwent randomization, and you had 99 that were assigned to the intervention group, which was lopinavir and ritonavir, and a hundred that were assigned to the standard care group.

有357位参与者经过了资格评估。有一些患者退出研究,剩下109例患者接受了随机分组,您有99例被分配为洛匹那韦和利托那韦的干预组,还有一百例被分配为标准护理组。

Like any good studies should do, they show you what the two groups were, and what their characteristics were. If you look up and down the lopinavir and ritonavir category, and the standard care, there really wasn’t much difference between them at all statistically, which means that the randomization was pretty good.

像任何好的研究都应该做的那样,它们向您展示了这两个群体是什么,以及它们的特征是什么。如果您在lopinavir和ritonavir类别以及标准护理中上下查找,那么从统计学角度来看,它们之间确实并没有多大区别,这意味着随机分组是相当不错的。

If you look at these, you can kind of get a sense about who these patients were, the median age in both of these was 58. There was a majority of males here, which we’ve seen before. Body temperature interestingly was not febrile.

如果您看这些,您可能会对这些患者是谁有所了解,这两个患者的中位年龄均为58岁。这里以前有很多男性,这是我们以前见过的。有趣的是,体温不高。

In terms of the median, 36.5 is not a fever; in terms of those that had a fever, we had 89 percent and 93%. We had a number of people that had respirations above 24, those who had a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 notice were a very very small percentage of people. So most of these peoples’ blood pressures are actually elevated.

就中位数而言,36.5不是发烧。就发烧而言,我们分别有89%和93%。我们有很多人的呼吸频率高于24,而收缩压低于90的人却是非常小的。因此,这些人中的大多数血压实际上都在升高。

The other thing that was interesting to note here is that the amount of people with relatively low white blood cells is pretty extensive. So typically this is what you’re going to see, and you can look at the other characteristics. When you look at the types of interventions that were done, you can see again pretty much similar going up and down the categories.

在此需要注意的另一件事是,白细胞相对较低的人数量很多。因此,通常这就是您要看到的内容,您可以查看其他特征。当您查看已完成的干预类型时,您会再次看到类别之间的相似性。

Let’s take a look at the results. Again, here we’ve got days on the x-axis, and we have the cumulative improvement rate that we see in greater than 2 points. So if this is working well, we should see that these things go up rather quickly. In fact, what we see here is that while there is some space between the lopinavir and the ritonavir, it is not statistically significant. So it turns out that this is a negative study. It did not show a difference between the lopinavir and ritonavir, and the control group, at least in these pretty severe hospitalized patients.

让我们看一下结果。同样,这里的x轴上有几天,我们看到的累积改进率超过2分。因此,如果运行良好,我们应该看到这些情况会很快上升。实际上,我们在这里看到的是虽然洛匹那韦和利托那韦之间有一定的间隔,但在统计上并不重要。因此,事实证明这是一项负面研究。至少在这些相当严重的住院患者中,洛匹那韦和利托那韦与对照组之间没有显示差异。

You can see here in terms of the viral load, which should be coming down very nicely over time. Again, no real difference between the intervention of lopinavir and ritonavir group and the control group.

您可以在这里看到病毒载量,随着时间的流逝病毒载量会下降得非常好。同样,洛匹那韦和利托那韦组的干预与对照组之间没有真正的区别。

So the authors drew this conclusion: in hospitalized adult patients with severe covid-19, no benefit was observed with lopinavir and ritonavir treatment beyond standard care.

因此,作者得出以下结论:在住院的重度covid-19成人患者中,使用lopinavir和ritonavir的治疗未见超出标准治疗的益处。

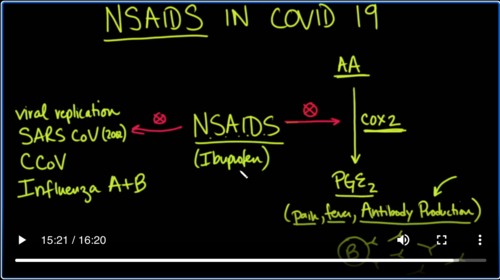

There’s been a number of questions about NSAIDs. The recent issue in terms of the French Minister saying that we should not use NSAIDs in covid-19. There’s also this really good summary of the key points that were put out by a pharmacist organization in Canada, which I will put a link to in the description below. The summary also goes through the salient points about the possible risks and benefits of NSAIDs in covid-19.

有关NSAID的问题很多。关于法国部长的最新一期报道说,我们不应该在covid-19中使用NSAID。还有一个加拿大药剂师组织提出的要点的非常好的摘要,我将在下面的描述中添加链接。该摘要还通过了有关covid-19中NSAID可能带来的风险和收益的要点。

But let’s talk a little bit about what NSAID is and what it has to do with viruses. So NSAIDs stand for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. For a long time, the thing that reduced inflammation was steroids. So these were a new category of medications that were not steroids, but they could reduce inflammation. Probably the earliest one that was invented was aspirin back in 1899. More on that one later. very importantly.

但是,让我们来谈谈什么是NSAID以及它与病毒的关系。因此,NSAID代表非甾体类抗炎药。长期以来,减少炎症的是类固醇。因此,这些是一类新的药物,不是类固醇,但可以减轻炎症。最早的发明者可能是1899年的阿司匹林。非常重要。

We’ll talk though about Ibuprofen. Ibuprofen is probably one of the most widely used NSAID in the world, and it’s used to reduce inflammation, reduce fever. It’s used for osteoarthritis, a number of indications for NSAIDs.

我们将谈论布洛芬。布洛芬可能是世界上使用最广泛的非甾体抗炎药之一,它可用于减轻炎症,减少发烧。它用于骨关节炎,许多NSAID适应症。

NSAIDs among other things have a special impact on an enzyme that we’re going to talk about, which is cox2. Cox2 stands for cyclooxygenase-2 as opposed to cyclooxygenase-1, which it also can inhibit, but that’s not really germane to our discussion.

NSAID除其他外对我们将要讨论的酶cox2产生特殊影响。 Cox2代表环氧合酶2,而环氧合酶1也可以抑制环氧合酶1,但这与我们的讨论没有真正的关系。

What does Cox2 do? It takes a substance called arachidonic acid, which will abbreviate AA, and it converts it into prostaglandins, specifically PGE2. Now coxswain also makes thromboxane, and that is used in platelets, but that’s not really germane to what we’re talking about.

Cox2做什么?它需要一种称为花生四烯酸的物质,它将缩写为AA,并将其转化为前列腺素,特别是PGE2。现在,考克斯温也可以制造血栓烷,用于血小板中,但这与我们所讨论的并没有真正的联系。

What we want to look at here is the cox-2 enzyme, which converts arachidonic acid into prostaglandin E2 now. Why is that important? Because prostaglandin E2 is involved with pain, which is why we would give it. It’s also involved with fever, which you would see in a viral infection, but it’s also involved in antibody production, or more specifically, cox-2 is involved in antibody production.

What NSAIDs do to that is they halt it. They prevent it. Antibodies are important; antibodies are made by B cells, and B cells make these antibodies to go out into the serum and attack things that should not be there; things like viruses.

So you could see why NSAIDs may cause a problem. Yes while they get rid of pain and fever, they can also hit your antibody production, but NSAIDs specifically ibuprofen and to a lesser extent other NSAIDs as well. They also have another function because they also inhibit some other things they could apparently can inhibit viral replication, and it’s been shown to hit the SARS-COV, not 2 but the original, the one that was from 2002.

It’s also been shown to attack the canine version of coronavirus, and it’s also been shown to be toxic and inhibitory to both influenza A and B. So the question is which one is it doing more and you can see why there might be benefits on either side and risks on either side.

What do we do? This pharmaceutical organization that put out this statement from Canada that was prepared a couple of days ago. They say here further research including randomized controlled trials is required to determine the impact of NSAIDS on coronavirus infection and subsequent disease.

They go on to talk about confounding variables. The NSAIDs could be treating comorbid conditions which put them at increased risk of more severe covid-19 disease. And so the bottom line is you need a randomized controlled trial. So I think the answer at this point

Is we don’t know based on this data. So then I did something really weird. I went back in time to an epidemic of a viral illness that was a pandemic and at the time they actually had an NSAID and it was given quite liberally and so the question is what happened at that time and what were the observations and it actually is really quite interesting.

And here’s a paper that was published in 2009 salicylates and pandemic influenza mortality 1918 to 1919 pharmacology pathology and historic evidence, and we’ll put a link to this as well in the description below and what it talks about is that aspirin at just come out in 1899, and it was a fresh drug to be used at the time. It was great way to get rid of fever and some people thought that if you could just treat the symptoms.

Terms of the flu the patient would get better and one of the big symptoms of the flu, of course was the fever the paper goes into discussing what the toxic dosages are today based on what we know at the time people would be given large doses of aspirin until they saw toxicity. Then they would sort of pull back they talk about four lines of evidence support the role of salicylate intoxication in 1918 influenza mortality, the pharmacokinetics the mechanism of action pathology and the fish.

Social recommendations for toxic regimens of aspirin immediately before the October 1918 deaths bike for those who don’t know one grain equals 65 milligrams. So when we talk about Grange, you’ll see the Aspen regimens recommended in 1918 are now known to regularly produce toxicities and you can read about that here. We do know that salicylates cause immediate lung toxicity and may predispose to bacterial infection by increasing lung fluid and protein levels and Imperial mucociliary clearance.

Lawrence and at the pathology of early deaths that we saw back in 1918 was consistent with Aspirin toxicity and a virus induced pathology and remember aspirin which is a salicylate is also an NSAID. So this kind of makes an interesting Twist on the discussion about whether we should be using NSAIDs in covid-19, and then interestingly its talks about the aspirin advertisements in August of nineteen eighteen and a series official recommendations for aspirin in September early, October.

Preceded the desk bike of October 1918 and it’s interesting that the young adults coming back from World War 1. We’re more likely they felt to take aspirin. Whereas the lower mortality in younger children may have been the result of less aspirin use and interestingly the major pediatric text of the time in 1918. And remember they have no antibiotics. They have no antivirals. They have no ventilators essentially what would happen in a major surge recommended not ask?

And not salicylate but actually recommended hydrotherapy for fever. These were the great thinkers working with what they had at that time and we can see at the time that there was a dichotomy that was set up in the treatment of the Spanish Flu back in the 1918-1919 those that really believed in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of aspirin and those that would treat with hydrotherapy. This is dr. William a Pearson in

18 I’m quote. None are so blind as those who cannot see that the average mortality of influenza patients treated by homeopathic Physicians was actually only about 130th and that’s a 30 not 13th, but one thirtieth of the average mortality reported by all Physicians and then Dr. C J lezail from Des Moines in 1999 says the German aspirin has killed more people than the German bullets have

So the question boils down to what are we getting in terms of risk benefits of these NSAIDs and ibuprofen or even aspirin are we confounding the mortality of 1918 with the dose of aspirin some would say yes is this just a larger magnitude of the effect that we might be seeing with NSAIDs with covid-19. I think it Bears testing. I think at this point we don’t have enough answers for that. I would say though that in my research of the night.

In 18 Spanish flu epidemic and pandemic. I think there are some parallels that we might be able to learn from because if in fact we do have a surge in this country, like what we are having in Italy the question is going to be what was it that worked back in 1918 and can we learn anything from there? Because we may very well be in a similar situation if we don’t have ventilators as they didn’t have if we don’t have pharmacological interventions as

as they didn’t have back then we don’t have antivirals as they didn’t have back then and don’t have antibiotics. In other words. Is there some lesson that we can learn from them that we could apply in our own homes for instance to improve survival. I think that bears thought and deserves research. Thanks for joining us.

Add comment